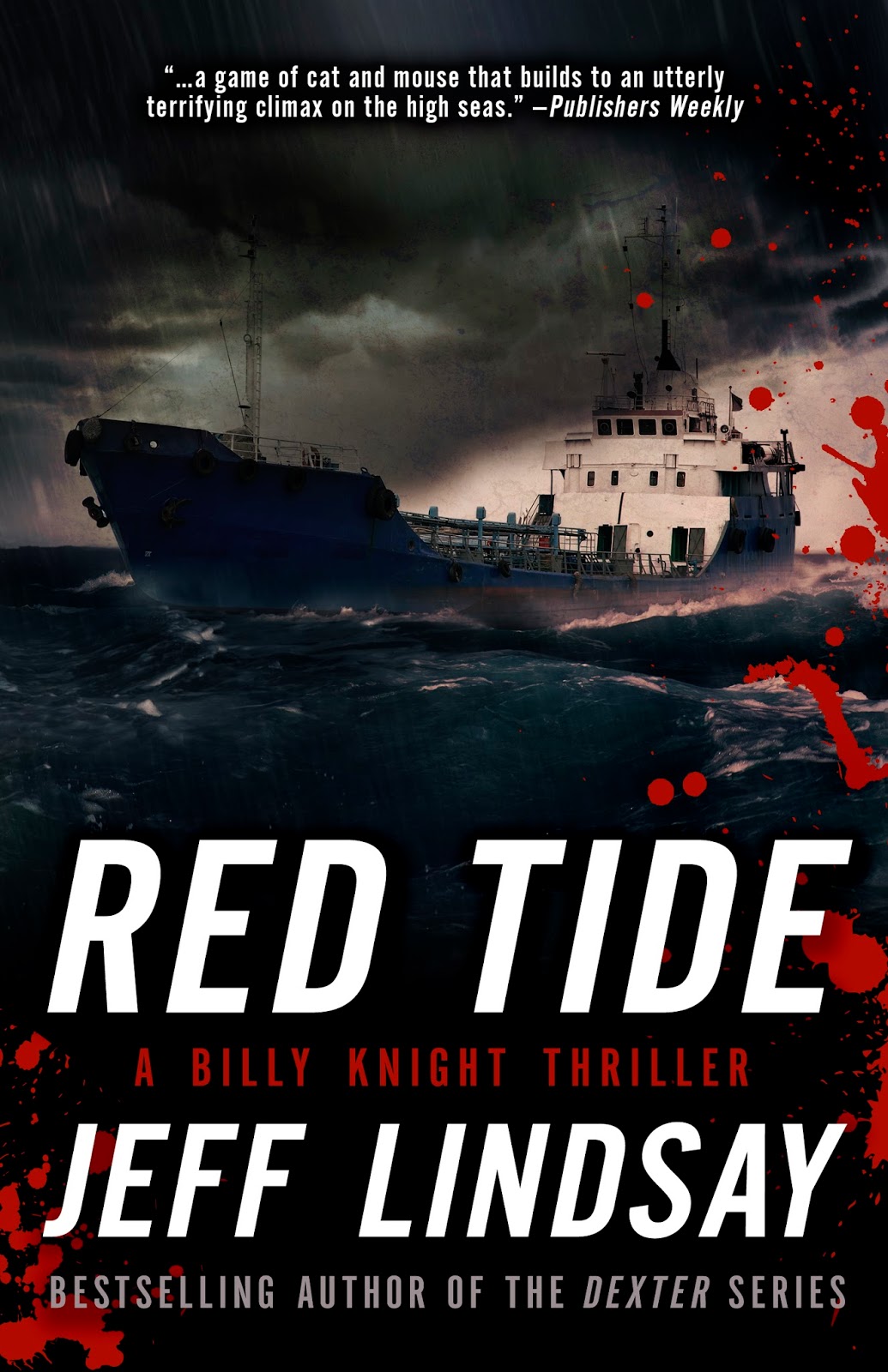

Red Tide

Jeff Lindsay

on Tour Oct 26 through Nov 11, 2015

Synopsis:

From Jeff Lindsay, the bestselling author of the Dexter series, comes the long-awaited sequel to his debut novel, Tropical Depression, featuring ex-cop Billy Knight.

Billy Knight wants to ride out Key West’s slow-season with the occasional charter and the frequent beer. But when he discovers a dead body floating in the gulf, Billy gets drawn into a deadly plot of dark magic and profound evil. Along with his spiritually-attuned terrier of a friend, Nicky, and Anna, a resilient and mysterious survivor of her own horrors, Billy sets out to right the wrongs the police won’t, putting himself in mortal peril on the high seas.

As the title of Lindsay’s latest book declares, Dexter is dead—the serial killer saga is over. Now, Red Tide offers fans of Jeff Lindsay a new thriller, one twenty years in the making.

Book Details:

Genre: Thriller

Published by: Diversion Publishing

Publication Date: October 27th 2015

Number of Pages: 228

ISBN: 1626817219 (ISBN13: 9781626817210)

Series: Billy Knight Thrillers #2

Purchase Links:

Watch the trailer here:

Read an excerpt:

Excerpted from Chapter 4 of

RED TIDE: A BILLY KNIGHT THRILLER

By Jeff Lindsay

Miami has this problem with its boaters. Some of them are still sane, rational, careful people—perhaps as many as three or four out of every ten thousand of them. The rest act like they escaped from the asylum, drank a bottle of vodka, snorted an ounce of coke, ate 25 or 30 downers and decided to go for a spin. Homicidal, sociopathic maniacs, wildly out of control, with not a clue that other people are actually alive, and interested in keeping it that way. To them, other boats are targets. They get in the boat knowing only two speeds: fast and blast-off.

I mentioned a few of these things to the boats that tried to kill me. I don’t think they could hear me over the engine roar. One of the boats had four giant outboard motors clamped on the back; 250 horsepower each, all going at full throttle no more than six inches from Sligo. If I had put the boom out I would have beheaded the boat’s driver. He might not have noticed.

“To get a driver’s license,” I said to Nicky through gritted teeth, “you have to be sixteen, take a test, and demonstrate minimal skill behind the wheel.”

Nicky was busy fumbling on a bright orange life jacket, fingers trembling, and swearing under his breath.

“To drive a boat—which is just as fast, bigger, and in conditions just as crowded and usually more hazardous—you have to be able to start the motor. That’s all. Just start the motor. There’s something wrong with this picture, Nicky.”

“There is, mate,” he said. “We’re in it. Can you get us out of here?”

My luck was working overtime. We had four more close scrapes—one with a huge Italian-built motor yacht that was 100 feet long, cruising down the center of the channel at a stately thirty knots, but I got us out of the channel alive and undamaged. When I cleared the last two markers and turned into the wind I told Nicky, “Okay. Raise the sails.”

He stared at me for a moment. “Sure. Of course. How?”

It turned out Nicky had never been on a sailboat before. So he held the tiller while I went forward to the mast and ran the sails up. Then I jumped back into the cockpit and killed the engine.

“Home, James,” said Nicky, popping two beers and handing me one. “It’s been a bitch of a morning.”

I took the beer and pointed our bow south.

It was a near-perfect day, with a steady, easy wind coming from the east. We sailed south at a gentle five knots, staring at the scenery. Cape Florida looked strange, embarrassed to be naked. All its trees had been stripped away by the hurricane. Farther south, the stacks of Turkey Point Nuclear Reactor stuck up into the air, visible for miles. It was a wonderful landmark for all the boaters. Just steer thataway, Ray Bob, over there towards all them glowing fishes.

• • •

The weather held. We made it down through the Keys in easy stages, staying the first two nights in small marinas along the way, rising at dawn for a lazy breakfast in the cockpit, then casting off and getting the sails up as quickly as possible. Part of the pure joy of the trip was in the sound of the wind and the lack of any kind of machine noise. We’d agreed to do without the engine whenever we could.

That turned out to be most of the time. Nicky took to sailing quickly and without effort. We fell into the rhythm of the wind and the waves so easily, so naturally, that it was like we had been doing this forever, and would keep doing it until one day we were too old and dry and simply blew gently over the rail, wafted away on a wave.

The third night we could have made it in to Key West. But we would have been docking in the dark, and working a little harder than we wanted to. So we pulled in to a small marina with plenty of time left before sunset.

Nicky used the time doing what he called rustling up grub. I don’t know if that’s how they say it in Australia, or if he heard it in some old John Wayne movie. From what he’d told me about Australia, there’s not much difference.

I sat in the cockpit with a beer, stretched out under the blue Bimini top, and waited for Nicky to get back. I had a lot to think about, so I tried not to. But my thoughts were pretty well centered on Nancy.

It was over. It wasn’t over. I should do something. I should let it take its course. It wasn’t too late. It had been too late for months. Eeny meeny miny mo.

Luckily, Nicky came back before I went completely insane. He was clutching a bag of groceries and two more six packs of beer.

“Ahoy the poop,” he shouted. “How ’bout a hand, mate?”

I got him safely aboard and he went below to the little kitchen. It sounded like he was trying to put a hole in the hull with an old stop sign while singing comic opera, so I stayed in the cockpit, watching the sun sink and thinking my thoughts.

There is something very special about sunset in a marina. All the people in their boats have done something today. They have risked something and achieved something, and it gives them all a pleasant smugness that makes them very good company at happy hour. A few hours later the people off the big sports fishermen will be loud obnoxious drunks and the couples in their small cruising sailboats will be snarling at them self-righteously from their Birkenstocks, but at sunset they are all brothers and sisters and there are very few places in the world better for watching the sun go down than from the deck of a boat tied safely in a marina after a day on the water.

I sipped a beer. I felt good, too, although my mind kept circling back to Nancy, and every time it did my mood lurched downwards. But it’s hard to feel bad on a sailboat. That’s one reason people still sail.

Anyway, tomorrow we would be home. I could worry about it then.

Early the next morning we were working our way towards Key West, about two miles off shore on the ocean side. We had decided on the ocean side because of the mild weather. With the prevailing wind from the east, we would have a better sail on the outside, instead of in the calmer waters of the Gulf on the inside of the Keys.

And because the weather was so mild, we went out a little further than usual. Nicky was curious about the Gulf Stream, which runs close to the Keys. I put us onto its edge, and by early afternoon we were only a few miles out of Key West.

Nicky had dragged up his black plastic box and, surprise, pulled out a large handgun.

Like a lot of other foreigners who settle in the USA, Nicky had become a gun nut. He was not dangerous, or no more dangerous than he was at the dinner table. In fact he had become an expert shot and a fast draw. The fast draw part had seemed important to him out of all proportion to how much it really mattered. I put it down to the horrors of growing up a runt in Australia.

Somehow Nicky managed to rationalize his new love for guns with his philosophy of All-Things-Are-One brotherhood. “Simple, mate,” he’d said with a wink, “I’m working out a past life karmic burden.”

“Horseshit.”

“All right then, I just like the bloody things. How’s that?”

Nicky had a new gun. He wanted to fire off a few clips and get the feel of it. Since we were out in the Stream and the nearest boat was almost invisible on the horizon, I didn’t see any reason why not. So Nicky shoved in a clip and got ready to fire his lovely new toy.

It was a nine millimeter Sig Sauer, an elegant and expensive weapon that Nicky needed about as much as he needed a Sharp’s buffalo rifle, but he had it and so far he hadn’t blown off his foot with it. I was hoping he would stay lucky.

“Ahoy, mate,” called Nicky, pointing the gun off to the south, “thar she blows.”

I turned to follow his point. A bleach bottle was sailing slowly out into the Gulf Stream.

“Come on,” Nicky urged, “pedal to the metal, mate.”

I tightened the main sheet and turned the boat slightly to give him a clear shot and Nicky opened up. He fired rapidly and well. The bleach bottle leaped into the air and he plugged it twice more before it came down again. He sent it flying across the water until the clip was empty and the bottle, full of holes, started to settle under.

I chased down the bottle and hooked it out with a boathook before it sank from sight. There’s enough crap in the ocean. Nicky was already shoving in a fresh clip.

“Onward, my man,” he told me, slamming home the clip and letting out a high, raucous, “Eeee-HAH!” as he opened a new beer. We were moving out further than we should have, maybe, out into the Gulf Stream. It’s easy to know when you’re there. You see a very abrupt color change, which is just what it sounds like: the water suddenly changes from a gunmetal green to a luminous blue. The edge where the change happens is as hard and startling as a knife-edge.

“Ahoy, matey,” Nicky called again, pointing out beyond the color change, and I headed out into the Gulf Stream for the new target. “Coconut!” Nicky called with excitement as we got closer. It was his favorite target. He loved the way they exploded when he hit them dead on.

I made the turn, adjusting the sheet line and again presenting our broadside, and swiveled my head to watch.

Nicky was already squinting. His hand wavered over the black nylon holster clipped to his belt. He let his muscles go slack and ready. I stared at the coconut. From fifty yards it suddenly looked wrong. The color was almost right, a greyish brown, and the dull texture seemed to fit, but—

“Hang on, Nicky,” I said, “Just a second—”

But the first two shots were already smacking away, splitting the sudden quiet.

I shoved the tiller hard over and brought us into the wind. The boat lurched and made Nicky miss his second shot. He looked at me with an expression of annoyance. I nodded at his target. He had hit the coconut dead center with the first shot. It should have leapt out of the water in a spectacular explosion. It hadn’t. The impact of the shot pushed it slowly, sluggishly through the water and we could both see it clearly now.

It wasn’t a coconut. Not at all. It was a human head.

RED TIDE: A BILLY KNIGHT THRILLER

By Jeff Lindsay

Miami has this problem with its boaters. Some of them are still sane, rational, careful people—perhaps as many as three or four out of every ten thousand of them. The rest act like they escaped from the asylum, drank a bottle of vodka, snorted an ounce of coke, ate 25 or 30 downers and decided to go for a spin. Homicidal, sociopathic maniacs, wildly out of control, with not a clue that other people are actually alive, and interested in keeping it that way. To them, other boats are targets. They get in the boat knowing only two speeds: fast and blast-off.

I mentioned a few of these things to the boats that tried to kill me. I don’t think they could hear me over the engine roar. One of the boats had four giant outboard motors clamped on the back; 250 horsepower each, all going at full throttle no more than six inches from Sligo. If I had put the boom out I would have beheaded the boat’s driver. He might not have noticed.

“To get a driver’s license,” I said to Nicky through gritted teeth, “you have to be sixteen, take a test, and demonstrate minimal skill behind the wheel.”

Nicky was busy fumbling on a bright orange life jacket, fingers trembling, and swearing under his breath.

“To drive a boat—which is just as fast, bigger, and in conditions just as crowded and usually more hazardous—you have to be able to start the motor. That’s all. Just start the motor. There’s something wrong with this picture, Nicky.”

“There is, mate,” he said. “We’re in it. Can you get us out of here?”

My luck was working overtime. We had four more close scrapes—one with a huge Italian-built motor yacht that was 100 feet long, cruising down the center of the channel at a stately thirty knots, but I got us out of the channel alive and undamaged. When I cleared the last two markers and turned into the wind I told Nicky, “Okay. Raise the sails.”

He stared at me for a moment. “Sure. Of course. How?”

It turned out Nicky had never been on a sailboat before. So he held the tiller while I went forward to the mast and ran the sails up. Then I jumped back into the cockpit and killed the engine.

“Home, James,” said Nicky, popping two beers and handing me one. “It’s been a bitch of a morning.”

I took the beer and pointed our bow south.

It was a near-perfect day, with a steady, easy wind coming from the east. We sailed south at a gentle five knots, staring at the scenery. Cape Florida looked strange, embarrassed to be naked. All its trees had been stripped away by the hurricane. Farther south, the stacks of Turkey Point Nuclear Reactor stuck up into the air, visible for miles. It was a wonderful landmark for all the boaters. Just steer thataway, Ray Bob, over there towards all them glowing fishes.

• • •

The weather held. We made it down through the Keys in easy stages, staying the first two nights in small marinas along the way, rising at dawn for a lazy breakfast in the cockpit, then casting off and getting the sails up as quickly as possible. Part of the pure joy of the trip was in the sound of the wind and the lack of any kind of machine noise. We’d agreed to do without the engine whenever we could.

That turned out to be most of the time. Nicky took to sailing quickly and without effort. We fell into the rhythm of the wind and the waves so easily, so naturally, that it was like we had been doing this forever, and would keep doing it until one day we were too old and dry and simply blew gently over the rail, wafted away on a wave.

The third night we could have made it in to Key West. But we would have been docking in the dark, and working a little harder than we wanted to. So we pulled in to a small marina with plenty of time left before sunset.

Nicky used the time doing what he called rustling up grub. I don’t know if that’s how they say it in Australia, or if he heard it in some old John Wayne movie. From what he’d told me about Australia, there’s not much difference.

I sat in the cockpit with a beer, stretched out under the blue Bimini top, and waited for Nicky to get back. I had a lot to think about, so I tried not to. But my thoughts were pretty well centered on Nancy.

It was over. It wasn’t over. I should do something. I should let it take its course. It wasn’t too late. It had been too late for months. Eeny meeny miny mo.

Luckily, Nicky came back before I went completely insane. He was clutching a bag of groceries and two more six packs of beer.

“Ahoy the poop,” he shouted. “How ’bout a hand, mate?”

I got him safely aboard and he went below to the little kitchen. It sounded like he was trying to put a hole in the hull with an old stop sign while singing comic opera, so I stayed in the cockpit, watching the sun sink and thinking my thoughts.

There is something very special about sunset in a marina. All the people in their boats have done something today. They have risked something and achieved something, and it gives them all a pleasant smugness that makes them very good company at happy hour. A few hours later the people off the big sports fishermen will be loud obnoxious drunks and the couples in their small cruising sailboats will be snarling at them self-righteously from their Birkenstocks, but at sunset they are all brothers and sisters and there are very few places in the world better for watching the sun go down than from the deck of a boat tied safely in a marina after a day on the water.

I sipped a beer. I felt good, too, although my mind kept circling back to Nancy, and every time it did my mood lurched downwards. But it’s hard to feel bad on a sailboat. That’s one reason people still sail.

Anyway, tomorrow we would be home. I could worry about it then.

Early the next morning we were working our way towards Key West, about two miles off shore on the ocean side. We had decided on the ocean side because of the mild weather. With the prevailing wind from the east, we would have a better sail on the outside, instead of in the calmer waters of the Gulf on the inside of the Keys.

And because the weather was so mild, we went out a little further than usual. Nicky was curious about the Gulf Stream, which runs close to the Keys. I put us onto its edge, and by early afternoon we were only a few miles out of Key West.

Nicky had dragged up his black plastic box and, surprise, pulled out a large handgun.

Like a lot of other foreigners who settle in the USA, Nicky had become a gun nut. He was not dangerous, or no more dangerous than he was at the dinner table. In fact he had become an expert shot and a fast draw. The fast draw part had seemed important to him out of all proportion to how much it really mattered. I put it down to the horrors of growing up a runt in Australia.

Somehow Nicky managed to rationalize his new love for guns with his philosophy of All-Things-Are-One brotherhood. “Simple, mate,” he’d said with a wink, “I’m working out a past life karmic burden.”

“Horseshit.”

“All right then, I just like the bloody things. How’s that?”

Nicky had a new gun. He wanted to fire off a few clips and get the feel of it. Since we were out in the Stream and the nearest boat was almost invisible on the horizon, I didn’t see any reason why not. So Nicky shoved in a clip and got ready to fire his lovely new toy.

It was a nine millimeter Sig Sauer, an elegant and expensive weapon that Nicky needed about as much as he needed a Sharp’s buffalo rifle, but he had it and so far he hadn’t blown off his foot with it. I was hoping he would stay lucky.

“Ahoy, mate,” called Nicky, pointing the gun off to the south, “thar she blows.”

I turned to follow his point. A bleach bottle was sailing slowly out into the Gulf Stream.

“Come on,” Nicky urged, “pedal to the metal, mate.”

I tightened the main sheet and turned the boat slightly to give him a clear shot and Nicky opened up. He fired rapidly and well. The bleach bottle leaped into the air and he plugged it twice more before it came down again. He sent it flying across the water until the clip was empty and the bottle, full of holes, started to settle under.

I chased down the bottle and hooked it out with a boathook before it sank from sight. There’s enough crap in the ocean. Nicky was already shoving in a fresh clip.

“Onward, my man,” he told me, slamming home the clip and letting out a high, raucous, “Eeee-HAH!” as he opened a new beer. We were moving out further than we should have, maybe, out into the Gulf Stream. It’s easy to know when you’re there. You see a very abrupt color change, which is just what it sounds like: the water suddenly changes from a gunmetal green to a luminous blue. The edge where the change happens is as hard and startling as a knife-edge.

“Ahoy, matey,” Nicky called again, pointing out beyond the color change, and I headed out into the Gulf Stream for the new target. “Coconut!” Nicky called with excitement as we got closer. It was his favorite target. He loved the way they exploded when he hit them dead on.

I made the turn, adjusting the sheet line and again presenting our broadside, and swiveled my head to watch.

Nicky was already squinting. His hand wavered over the black nylon holster clipped to his belt. He let his muscles go slack and ready. I stared at the coconut. From fifty yards it suddenly looked wrong. The color was almost right, a greyish brown, and the dull texture seemed to fit, but—

“Hang on, Nicky,” I said, “Just a second—”

But the first two shots were already smacking away, splitting the sudden quiet.

I shoved the tiller hard over and brought us into the wind. The boat lurched and made Nicky miss his second shot. He looked at me with an expression of annoyance. I nodded at his target. He had hit the coconut dead center with the first shot. It should have leapt out of the water in a spectacular explosion. It hadn’t. The impact of the shot pushed it slowly, sluggishly through the water and we could both see it clearly now.

It wasn’t a coconut. Not at all. It was a human head.

Jeff Lindsay Guest Post

“I’ve got a great idea for you!”

These

are words that strike terror into every writer’s heart. Or if not terror, at

least really strong crankiness. And when this phrase is inevitably followed by,

“You write it and we’ll split the money!”

the crankiness morphs into an overwhelming urge to sink one’s fangs into

the speaker’s jugular.

I

hear these dread words every time I dare stick my head out the front door, and

I have come to loathe them entirely. Still, somehow I always find the intestinal

fortitude to smile and say no thanks; I am very proud that I have never once

ripped out a throat for this heinous offense.

You

may wonder at the ferocity of my feelings. Where’s the harm, you may ask, in a

well-meaning person offering me their idea? Isn’t it, after all, a friendly

gesture?

No.

It is not. Not to me.

In

the first place, I don’t need your idea. I have far too many of my own. People

seem to assume that writers wander around all day frantically searching for

ideas, like bloodhounds looking for a scent. The truth is just the opposite. I

have a huge stack of ideas that I love. I get more of them every day of my

life. Every time I read the paper, turn on the TV, listen to NPR News, I get

more ideas. My real problem is keeping all of them at bay and concentrating on

what I’m supposed to be writing.

And

in the second place – if people think that having an idea is as rare, difficult

and valuable as turning that idea into a novel, why don’t they just write the

damn thing? Then they can keep all that money for themselves.

And

in the third place – what money? Where is it coming from? My agent doesn’t want

me writing your idea; he’ll disown me. Neither does my publisher; he wants the

book for which we’ve both signed a contract. My lawyer doesn’t want me anywhere

near your idea; the possibilities for litigation are so numerous it would turn

into a life-long legal career.

I

had a great teacher many years ago, a Romanian man named Radu Penciulescu. He

used to say, “Ideas are cheap. It’s defending them that matters.” By defending

he meant making them work, proving that the idea deserved to use up your time

and creative energy and come to life. Radu was right; defending an idea is hard

work, especially at novel length. It takes ferocious concentration, a fierce belief

in the idea, and a true passion to make it work. Like most long-time

professional writers, I can summon concentration and fake the belief. I hate it

like poison, but once or twice when the rent was overdue, it was necessary.

But

I can’t, I won’t, fake passion. It demeans me and makes me feel soiled.

Does

this seem precious? Sorry – but I’ve devoted my entire life to writing. I have

to believe it means something; not just books, but the very act of writing. And

if it does, it’s because it’s a vocation – which means, a calling, like being a

priest. Try telling a Catholic priest you have a great ritual for worshipping

Moloch – would he like to perform it? He may excommunicate you, or at least

exorcise you.

I

feel the same. Writing is my church, and the ideas – my ideas – are Communion.

I’m glad to share them with you. But I don’t want your idea, no matter how good

it is.

It’s

the wrong religion.

Author Bio:

Jeff Lindsay is the award-winning author of the seven New York Times bestselling Dexter novels upon which the international hit TV show Dexter is based. His books appear in more than 30 languages and have sold millions of copies around the world. Jeff is a graduate of Middlebury College, Celebration Mime Clown School, and has a double MFA from Carnegie Mellon. Although a full-time writer now, he has worked as an actor, comic, director, MC, DJ, singer, songwriter, composer, musician, story analyst, script doctor, and screenwriter.

Jeff Lindsay is the award-winning author of the seven New York Times bestselling Dexter novels upon which the international hit TV show Dexter is based. His books appear in more than 30 languages and have sold millions of copies around the world. Jeff is a graduate of Middlebury College, Celebration Mime Clown School, and has a double MFA from Carnegie Mellon. Although a full-time writer now, he has worked as an actor, comic, director, MC, DJ, singer, songwriter, composer, musician, story analyst, script doctor, and screenwriter.

Catch Up:

Tour Participants:

Giveaway:

This is a giveaway hosted by Diversion Books for Jeff Lindsay. There will be 5 winners of 1 eBook copy of RED TIDE by Jeff Lindsay. The giveaway begins on October 26th, 2015 and runs through November 11th, 2015. a Rafflecopter giveawayGet More Great Reads at Partners In Crime Virtual Book Tours

Today's Gonereding item is:

Every mystery lover needs a

Sherlock Holmes finger puppet

Click HERE for the buy page

Thanks for featuring this new series thriller and introducing us to the author. A very interesting guest post!

ReplyDeleteThanks Lance

DeleteLOL You know, I never thought about how often writers probably hear that phrase. I guess it comes with the territory right? Great guest post!

ReplyDeleteI know Ali I never thought of that either

DeleteOh this book sounds very interesting

ReplyDeleteGood Luck to everyone!

xx

www.sakuranko.com

Hi, Thanks for the comment and I love your blog!

DeleteI have Tropical Depression and look forward to slipping into it. Great post Debbie!

ReplyDeleteOh No Kim, stay safe!

DeleteI never could get into the Dexter TV show. No idea why because I love anything to do with serial killers :/

ReplyDelete